Yvan Gelbart

,

Lead Analyst

Author

, Published on

September 19, 2025

Sarah McLean

,

Lead Content Manager

Co-Author

Spinergie analyst Yvan Gelbart examines the key differences between the current and previous generations of heavy lift wind installation vessels.

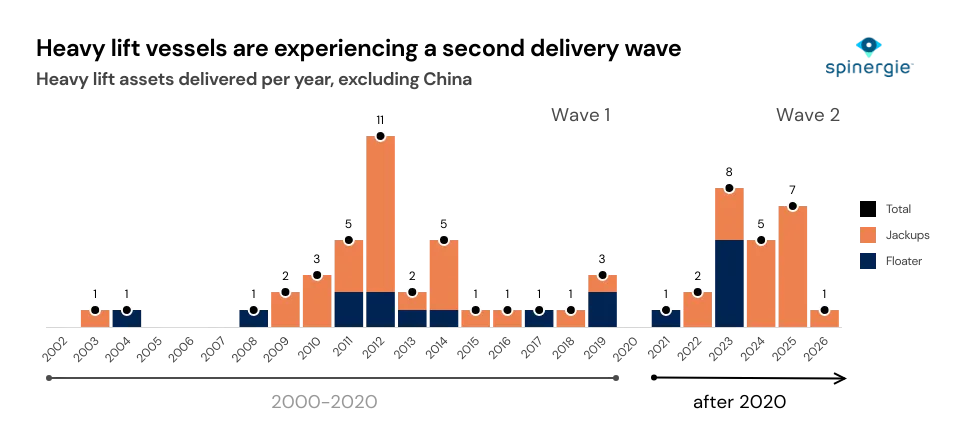

In the current heavy lift market, Spinergie indexes that 62 heavy lift vessels have been delivered since the turn of the millennium, with jackups and floaters now both involved in the offshore wind market to various degrees.

The deliveries of these vessels have been observed within two distinct waves in which a large number of assets have had overconcentrated delivery dates within a few years. The first wave peaked in 2012, with 26 assets delivered over the course of five years. The second and current wave totals 23 vessels. Each of these waves has been influenced by shortages in vessel supply and high market demand. Despite just over a decade between the two generations, jackups and floaters have each already evolved to adapt to larger turbines and heavier foundations, albeit in different ways. Here, we examine the evolutions of these two heavy lift segments.

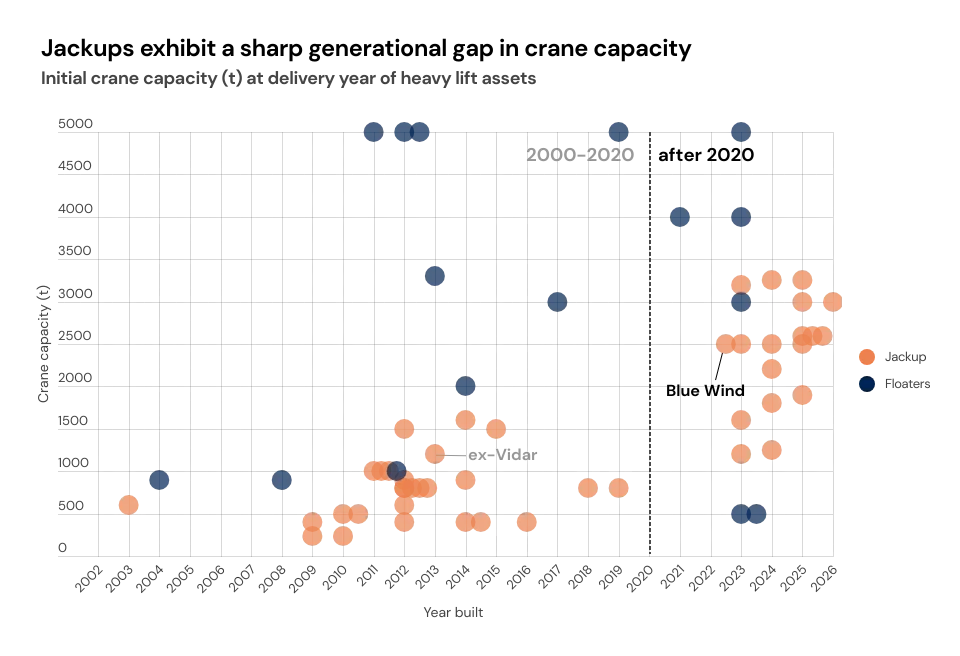

Crane capacities and capabilities in the jackup and floater heavy lift sectors have evolved across the two newbuild waves, but they have some major differences.

The heavy lift jackups delivered in the 2010s were typically sized for 8 MW turbines, meaning crane capacity of between 800t and 900t was the norm. Several of these vessels have recently undergone crane upgrades to 1,600t to better suit the market's current tasks.

During that first wave in the 2010s, heavy lift assets were built with the expectation that offshore wind would see an escalation in size requirements, but there remained a cautious outlook on long-term growth. This was observed with Jan De Nul’s acquisition of Hochtief’s Vidar [now Vole Au Vent] in 2015. Saying at the time, “The Vidar is perfectly usable in sectors other than wind power.” Since purchase, the 2013-delivered vessel, which is equipped with a 1,200t crane, has spent 100% of its time in the offshore wind sector, highlighting that growth expectations have been met.

The new generation of jackups has seen crane capacities double. Shimizu’s Blue Wind, a 2,500t capable WTIV, was delivered in late 2022 as the first of a series of jackups made to install turbines up to 20 MW in nominal capacity.

For jackups, the median crane capacity at delivery is now 2,500t, representing a 213% increase from the 2000-2020 generation. These new cranes come with a 62% higher reach and longer booms. Additionally, WTIVs are becoming more suited to deeper waters as projects move farther from the shore (with jackups over 35% in max water depth).

Heavy lift floater crane specs have grown by a smaller margin than in jackups, as floaters previously involved in offshore wind already had impressive capabilities. Most older assets, such as Heerema's Thialf (1985-built), came from the oil and gas industry, while newer floaters are often purpose-built for offshore wind.

While cranes did not grow in raw capacity, the equipment onboard vessels has evolved. Heave-compensated and/or tiltable pile grippers have enabled more technically challenging installations of monopiles. Innovative crane placement on the vessel’s bow, exemplified by Seaway 7’s Alfa Lift, liberates a large amount of deck space to be used for carrying more components. Additionally, floaters now increasingly include HLCs, such as the Jumbo Javelin, which is equipped with smaller cranes and is better suited for installing transition pieces.

Like with crane capacities, the size of heavy lift vessels has also increased, but once again, some key differences have been observed between jackups and floaters.

When comparing hull specs between the two generations of jackups, we see that they have doubled in deck space. Prompted by growth in turbine sizes that require more space to fasten blades, towers, and nacelles, the median jackup of today has 108% more deck space than the 2000-2020 generation, at 5,200 square meters.

To create the deck space, vessels grew in length (36%) and width (40%), becoming slightly wider overall. Today, a typical jackup is 148 by 56 meters.

However, the dominant crane position has remained leg-encircling, which is preferred to save deck space.

Floaters have mostly grown in length (by 19%) between the older and newer generations. The lengthening of these vessels has also added a third to the deck space to see a current median of 7,400 m2 compared to 5,700 m2 in the previous generation. These larger, newer assets are now suitable for carrying longer monopiles.

The crane location has changed. In most vessels, it is now centered as opposed to on the side in the earlier generation.

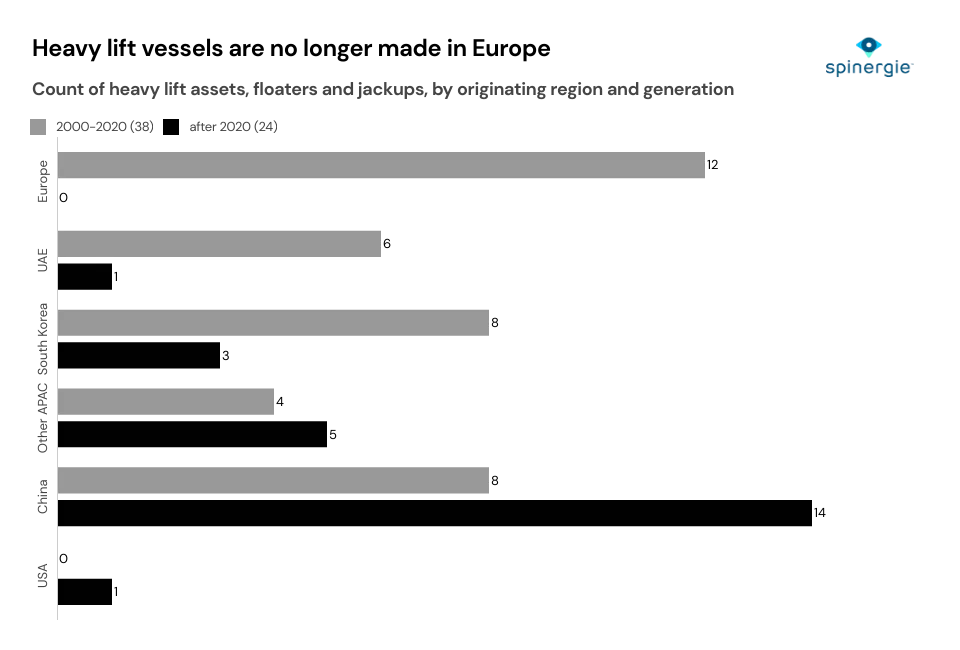

As a final note, we can return to Jan De Nul’s Vole Au Vent, a vessel that is truly an example of its time. The vessel was built at Crist, Gdansk, Poland, prior to delivery in 2013. Being built in Europe was not an exception, as it was accompanied by a wave of ships fresh out of shipyards in Romania, Croatia, and the Netherlands.

But now, ten years later, Europe is no longer delivering the hulls of heavy-lift vessels. Still, European yards often handle the crane installation part after the vessel is delivered from its shipbuilding yard.

The majority of the production is now done in China, with COSCO and China Merchants Heavy Industry taking the lion’s share. They enjoy a series of orders from fast-growing pure players like Cadeler. Lamprell in the UAE has conversely dramatically slowed its activity and is now focusing on offshore structures instead.

South Korea and APAC countries have kept production steady—but with a twist. Instead of sailing to Europe, heavy lift vessels now stay to work in the region. Last year, APAC took delivery of four WTIVs, which are now all employed locally.

The USA is a trendy newcomer. Cornered by the Jones Act, developer Dominion Energy is the sole company to create a US-built, flagged, and crewed heavy-lift jack-up. Charybdis was launched in April 2024 and will enter the active fleet next year.

Analysis of the subsea vessel fleet including its resurgence of interest and expectations for the future.

.jpg)

Maersk’s Sturgeon WTIV was set to be a pioneering Jones Act-compliant vessel for the US offshore wind market. Yet, with the domestic market faltering under the new administration the project was terminated just before delivery. Is this a sign of the wind market replicating the offshore rig glut of the mid-2010s? Spinergie’s Lead Analyst, Yvan Gelbart, presents his analysis.